The immune system is a major part of the body involved in protecting us from infections and from cancers. Unlike other organs where the cells and tissues stay in one place (the heart or the kidneys) the cells of the immune system move around the body either to monitor for signs of infection or to fight infection or destroy cancer cells.

Many different types of cells and separate organs make up the immune system. The major components are the bone marrow and thymus (a small organ in the neck) which produce many immune system cells and the spleen (in the abdomen) and the lymph nodes (scattered throughout the body – these are the so called “glands” that swell in the neck or elsewhere when you have an infection) that play a major role in “programming” parts of the immune system.

The immune system is divided into two major parts called the innate and the adaptive.

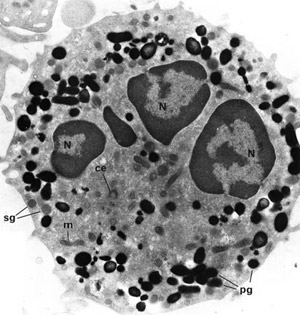

The Innate immune system reacts to infections and cancer cells in a pre-programmed way by recognising signals that activate the immune cells to destroy cells or infections with warning signs on them. Neutrophils and macrophages and natural killer cells are the main parts of the innate immune system.

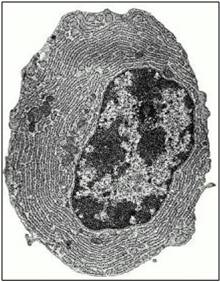

The Adaptive immune system is the part of the immune system that can learn to recognise almost any different infection and has to be programmed by the body. This part of the immune system is constantly changing throughout our lives as we encounter new infections, learn how to deal with them and remember them for the future. When we use vaccines we are programming the adaptive immune system to recognise a possible future infection. The adaptive immune system can recognise almost any possible infection by constantly making new cells that are all different. On each cell is a receptor that can match any possible protein or cell component from an infection (in the way a key fits a lock) and when the cell finds its match it can become activated to start making antibodies (if it is a B cell) or making new cells that will direct and control the immune system (if it is a T cell). Unfortunately because the cells can recognise almost anything they may also become activated by parts of our own bodies (this is called autoimmunity). The immune system contains many very specialised systems to prevent cells that recognise our own bodies from becoming activated but sometimes these systems may not work properly and this can lead to autoimmune disease.

Once the immune system has become activated there are many different substances produced by both the immune system and the cells in the place where the infection is. These control the responses by activating cells and summoning more immune system cells to the site of the problem. Some of these substances are proteins called cytokines or chemokines and some treatments for inflammatory diseases block their action to reduce the activation of the immune system.

Unfortunately most treatments for autoimmune diseases and vasculitis cannot specifically target the parts of the immune system causing the problem. Most treatments have a general effect of reducing the activation and effectiveness of the immune system to a greater or lesser extent. This accounts for the main serious short and long term effects of treatment of an increased susceptibility to infections and the small long term increased risk of cancer associated with some treatments.

Usually when doctors are considering the most appropriate treatment for a particular patient they will be trying to get the right balance between suppressing the immune system enough to stop the disease causing damage and long term problems but not suppressing it so much that the risk of infections and cancer is too high. Often the right balance changes over time as the disease comes under control and less strong treatment can be used to keep control of the disease without causing so much suppression of the immune system function.

Further Reading: “A Beginner’s Guide to the Immune System“